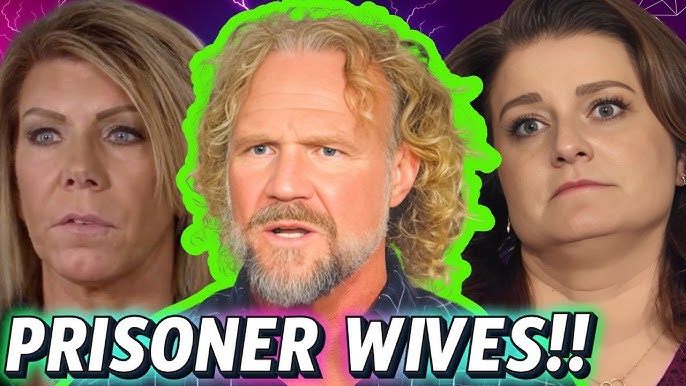

‘i don’t want to get in trouble’ — sister wives exposes a toxic marriage dynamic”

“I don’t want to get in trouble” sounds harmless on the surface, almost childish, but within the context of Sister Wives it detonates like a quiet confession, exposing a toxic marriage dynamic that has been hiding in plain sight for years, because when an adult woman in a supposedly consensual, faith-driven plural marriage says those words about her own husband, what she’s really revealing is fear, conditioning, and a power imbalance so normalized that it barely registers as abuse to those living inside it. That sentence isn’t about rules or respect, it’s about punishment, emotional withdrawal, favoritism, and the invisible consequences that follow whenever obedience slips, and once viewers truly sit with that phrase, it becomes impossible to unsee how deeply it permeates the entire family structure. Trouble, in this context, is never clearly defined, which is precisely what makes it so effective as a control mechanism, because it can mean loss of affection, public shaming, reduced time, financial consequences, or being quietly pushed out of favor, all without a single rule ever being spoken aloud. Over time, the wives learn to self-police, to anticipate moods, to edit their feelings, to suppress needs before they are even voiced, and that internal censorship becomes a survival skill disguised as loyalty. The most disturbing aspect is that this dynamic isn’t enforced through yelling or overt threats, it’s enforced through silence, through icy withdrawal, through the sudden emotional absence that teaches the wives exactly how replaceable they are in a system where love is conditional and hierarchy is everything. When one wife admits she doesn’t want to get in trouble, she’s not just speaking for herself, she’s articulating the unspoken rulebook governing the entire family, a rulebook written not in words but in consequences observed over decades. The husband at the center of this dynamic rarely needs to assert control directly because the structure does it for him, rewarding compliance with attention and punishing dissent with neglect, and that kind of intermittent reinforcement is psychologically devastating, creating a cycle where approval feels addictive and disapproval feels catastrophic. What makes the situation even more insidious is how spirituality and doctrine are used to sanctify the imbalance, framing obedience as virtue, endurance as strength, and suffering as proof of commitment, effectively trapping the wives in a moral maze where leaving or pushing back feels not just disloyal but sinful. Over time, individuality erodes, because expressing discomfort risks destabilizing the fragile peace, and peace is always prioritized over truth, especially when truth threatens the authority of the person at the top. Viewers watching from the outside may wonder why the wives didn’t simply speak up sooner, but that question misunderstands how deeply this kind of conditioning runs, because when someone’s emotional safety, financial stability, social identity, and spiritual worth are all tied to one person’s approval, the cost of honesty becomes terrifyingly high. The phrase “I don’t want to get in trouble” reveals that the marriage was never a partnership of equals, it was a compliance-based system where autonomy was tolerated only as long as it didn’t challenge the power structure, and any deviation was quietly punished until conformity was restored. What’s especially chilling is how normalized this became, how often discomfort was reframed as jealousy, insecurity, or personal failure rather than a rational response to inequality, and how the wives were subtly encouraged to compete for approval rather than unite in solidarity, ensuring the system remained intact. The emotional labor required to survive in such a dynamic is immense, constantly managing tone, timing, and expression, constantly calculating whether a thought is worth the risk of fallout, and over time that vigilance takes a profound psychological toll, manifesting as anxiety, self-doubt, and a shrinking sense of self. When cracks finally began to show publicly, they weren’t sudden or dramatic, they were quiet admissions like this one, moments where the mask slipped just enough to reveal the fear underneath, and those moments were far more damning than any explosive argument ever could be. The real tragedy is that for years this dynamic was presented as functional, even aspirational, obscuring the reality that love cannot thrive where fear governs behavior, and consent cannot be meaningful when one party controls the consequences of dissent. The exposure of this toxic pattern forces a reckoning not just with one marriage, but with the broader narrative that endurance equals virtue and that women must minimize themselves to keep families intact. Once viewers recognize the weight behind “I don’t want to get in trouble,” they begin to reexamine every interaction, every apology, every instance of self-blame, and a far darker picture emerges, one where emotional safety was never guaranteed and where love was rationed as a reward rather than given freely. In the end, that single sentence becomes a thesis statement for the entire unraveling, because healthy relationships don’t require fear-based compliance, they don’t train adults to speak like children bracing for punishment, and they don’t confuse control with leadership. What Sister Wives ultimately exposes through this moment isn’t just the failure of one marriage, but the quiet, corrosive danger of systems that prioritize hierarchy over humanity, and once that truth is seen, it cannot be unseen, because the most devastating toxicity is not the kind that explodes loudly, but the kind that whispers softly, teaches you to be smaller, and convinces you that silence is love.